By Heather N. Smith

I. Introduction: The Curation of the Artist Persona, Then and Now

“That’s my real name—my real name’s Britney Jean Spears.” Britney Spears’s 1998 DVD special, Time Out with Britney Spears presents a typical example of how an audience might be introduced to an emerging pop star in the late 1990s. Wearing a lilac blouse, surrounded by a vase full of pink flowers, Spears is the picture of girlish charm and innocence. Her soft, overly sweet speaking voice and Southern accent further convey this image of early adolescent innocence. Spears answers a series of carefully crafted questions which are unheard by the audience and delivered by an off-camera interviewer. She demurs “Well I grew up in a really really small town. It’s called Kentwood and it’s like an hour away from New Orleans. I’m a Southern girl and I’m used to Cajun food and um blues music.”[1] Prompted by the interviewer, Spears further elaborates “um the population of my hometown is like 1200 people…it was like really small, it’s really really small.”[2]

This form of promotion whereby an artist would speak to their audience through carefully scripted filmed interviews was typical of the pop-scene pre-social media. Additionally, artists would often be consigned to cross-promote their label-mates in a similarly scripted manner. Britney Spears’s debut album contains a hidden track with her personally endorsing the music of the Backstreet Boys’ upcoming album release and playing samples.[3]

Thus, the last twenty years have witnessed a monumental shift in the curation of the artist persona. In this era, pop star appearances, interview questions, and promotional material, like this DVD, were carefully designed to present and control exactly the image that record companies wished to project. As Diane Hughes, Mark Evans, Guy Morrow, and Sarah Keith have observed in their book The New Music Industries: Disruption and Discovery, this promotional model was linear in nature with “gate-keepers”—most often the artist’s record label—controlling the artist’s narrative (See figure 1, linear model).[4]

Figure 1

The advent of social media has altered the landscape of the music industry dramatically on myriad levels. While the impact of social media upon musical production, marketing, and reception has been well explored within the fields of communication and cultural studies, this is a relatively unexplored topic within the field of musicology. Even lesser explored is how recent fan platforms, such as apps like Taylor Swift’s The Swift Life, have impacted artists’ ability to curate and control their own life and career narratives. This study aims to fill this gap in the literature, exploring questions such as: how does an artist’s publicizing of their private life on social media impact the creation and reception of their music? Furthermore, how does an artist’s public persona interact with their music in cases where references are explicit in their song lyrics? For instance, would a song like “Bad Blood,” in which Taylor Swift tacitly references a feud with Katy Perry that largely played out over social media, have been written in the days of Britney Spears’s early career? While it is impossible to know with certainty, this study argues that songs such as “Bad Blood” have been facilitated through the culture of social media, enabling artists to connect their social media persona with their music. As such, the fundamental impact of social media upon the production and reception of music deserves more scholarly attention in the discipline of musicology.

Diane Hughes, Mark Evans, Guy Morrow, and Sarah Keith have recently proposed a circular model of music marketing which has developed as a by-product of the digital age of music (See Figure 2).[5] Applying this model as a framework, I will demonstrate how the pop star’s social media presence and the production and reception of their music have become linked to an unprecedented level. Social media has, in some cases, changed the manner in which artists compose their music. Additionally, I argue that recent apps like Swift’s The Swift Life represent a new linear model whereby artists have created self-contained platforms that mimic the infrastructure of social media sites to act as a method of controlling fan engagement, as well as collecting information for marketing purposes. Taylor Swift is the central subject of this study for the sheer diversity of how her persona has transformed over the trajectory of her career. I analyze selected songs and music videos by Swift, as well as their reception history on various digital and social media platforms, such as Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and fan forums, and in interviews and entertainment news articles. Through this analysis, I illustrate the impact of social media on the production, marketing, and reception of music in three broad areas: the cultivation of persona, celebrity feuds, and fandom. These areas will at times overlap, as they often intersect. For instance, Taylor Swift’s song lyrics are often analyzed by entertainment news platforms, as well as disseminated by fans on her fan forums. Moreover, her songs are constantly analyzed for veiled references to her social media feuds with celebrities or to content that she has posted on social media, such as snake symbols. Thus, there is a melding of her music with her social media persona, rumoured feuds with various celebrities, and her connection to her fans.

Figure 2

“Country Roots” and Career Beginnings

Taylor Alison Swift (b. 1989) was born and raised in Pennsylvania. She rose to prominence at age 16 with her self-titled country debut album. Swift’s persona has shifted markedly over her career. Her 2014 album 1989 represented a dramatic shift from country to pop star, as well as the beginnings of veiled references to her feuds with other celebrities, which have continued on her most recent album, aptly entitled, Reputation. The album has inspired much social media speculation as to the celebrity feuds it references.[6] Though she released her first studio album in 2006, her online presence as an up-and-coming singer/songwriter dates back to the tender age of twelve. Internet Archive shows the earliest version of her artist website as June, 2002. Here, her biography reads that she is a sixth-grader with a “natural country sound.”[7] The authenticity of Taylor Swift’s country persona generated significant online debate in the past, with some arguing that she was not “country” as she did not hail from the “South” but from Pennsylvania.[8] While this issue of authenticity is somewhat subjective, what can be said with certainty is that her accent—both in speech and in song—has transformed along with her music. In early interviews from 2006-2008, Swift spoke with a relatively thick “country” accent, while in recent years she shows no trace of “country” in her speech.[9] This section examines these differences in her persona between the beginnings of her career and recent years as evinced through two songs, “Tim McGraw,” her first single from 2006’s album, Taylor Swift, and “Shake It Off”, from the album 1989. I will focus particular attention on imagery in the lyrics, instrumentation, music videos for the songs, and Swift’s vocal delivery. These two songs demonstrate how social media has increasingly influenced Swift’s compositional and production style, as well as the marketing of her music via social media.

Tim McGraw

Taylor Swift’s first single “Tim McGraw,” released in June 2006, introduced her to her listeners as an “authentic” country artist. As musicologist Travis Stimeling has observed, the song intentionally references a canonical figure of country music by creating an immediate association in the title between Taylor Swift and country music star, Tim McGraw.[10] This association is further constructed through the lyrics to the hook of the song in the chorus “When you think Tim McGraw, I hope you think of me.” This line is emphasized through its placement at the end of the chorus.[11] Thus, in spite of Swift’s official story that the lyrics detail a teen romance that ended at the close of summer which is remembered through an unspecified song by Tim McGraw, there appears to be an intentional attempt to construct an association between a famed figure of country music and Swift herself. That she opts to write the song in second person using “you” further adds to the double-layered meaning beneath the lyrics. The “you” in “I hope you think of me” can be just as easily be perceived as an address to her listening audience.

In addition to associations with Tim McGraw, the song constructs imagery which draws upon clichéd scenes of country life in the Deep South in the lyrics and the music video for the song, as well as through Swift’s vocal delivery. In spite of Swift’s upbringing in Pennsylvania, the song begins with a setting in the Deep South of Georgia. Throughout the song, the lyrics are delivered with a heavy southern accent. Swift pronounces words like “shined” and “night” with the “ah” vowel sound (0:14). Additionally, she diphthongizes the endings of words such as “happiness” and “dress”, making –ess endings two-syllables, in a style characteristic of many types of Southern accents (1:02). [12] The song is book-ended with the lyrics: “He/you said the way my blue eyes shined/Put those Georgia stars to shame that night.” If this image of the “authentic” South was not clear, the next line references a “chevy pick-up truck with the tendency of getting stuck, effectively conjuring up the image of a southern small-town romance between two teens of modest middle-class backgrounds (0:27).[13]

The imagery of the lyrics is echoed in the music video, which features Swift lying in the grass reminiscing about her lost love, who is seen in a flashback in the aforementioned Chevy pick-up truck, driving through back roads in the country. Another scene has Swift sitting on the ground with her back leaned up against a faded barn strumming her 12-string guitar (1:23).[14] Thus, the song constructs a persona of Taylor Swift as an “authentic” country artist through lyrical and visual imagery in the lyrics and music video, Swift’s vocal delivery, and the association of the song with a famed figure of country music. This carefully-crafted introduction of Swift to the music world is primarily linear in nature as it is a controlled, one-way interaction with the listening audience. It is important to establish this beginning to Swift’s career as a means of examining the impact of social media upon her compositional style. While there subtle double-meanings in the lyrics which build associations between her country persona and a famous figure of country music, there is no third person referencing of her audience, which was to become a prominent feature of her later works.

Taylor Swift and the Culture of “Haters”

Taylor Swift’s 2014 album 1989 marked a pivotal turning point from country to pop music. Her lead single “Shake It Off” illustrates the influence of social media upon artist production, marketing, and reception. The lyrics to the song center around what Swift has called “take-down culture,” which she sees as the pervasive tendency in Western culture toward the public criticism of both celebrities and non-celebrities alike.[15] The lyrics begin with Swift addressing the many criticisms she has faced as a celebrity, such as “staying out too late” and “going on too many dates.” Rather than refute these rumours, she instead switches gears, rising above it all, and “shaking it off.”[16]

While the song’s popularity may make it seem like a trite subject for musical analysis, it exemplifies several significant facets underlying the curation of the artist persona in the age of social media. Unlike her earlier works which largely exist within the typical country or pop framework of singer and love interest, “Shake It Off” is keenly aware of the outside word, and specifically of her critics. The song is in essence a declamation to Swift’s detractors as well as her fans. As she says in her interview for the song’s official release: “You have to not only live your life in spite of people who don’t understand you, you have to have more fun than they do.”[17]

In addition to the music itself, the marketing of the song reveals the depth of social media’s influence. The song was premiered via a livestream on Yahoo! after a lead-up campaign that included teasers on social media, as well as secret sessions which gave her most devoted fans a private listening party prior to the album’s official release. As Clyde Philip Rolston, Amy Macy, Tom Hutchison, and Paul Allen have noted, Swift’s deft promotion of 1989, harnessed the buying power of her massive social media audience, enabling the album to sell 1.3 million copies in its first week alone. This is an exceptionally high number in an era where the sale of music is often challenged due to its widespread availability online.[18] While these aspects of viral marketing display the prominent place of social media in artist promotion, perhaps the most significant indicator lies in the music video itself. Among the diverse group of hip-hop and ballet dancers are 100 of Swift’s fans.[19] The song’s lyrical premise of “telling off” her detractors is once again echoed in the recruitment of a “fan army” of sorts in the video (3:07). That these fans were selected via social media demonstrates the circular model of music marketing. There is interconnectedness from artist, to fans, to industry, as the artist’s musical output intersects with her social media persona, and actively involves fans in the process of performing and marketing the song.

In this scenario, the artist reaches out to her fans and detractors in a self-aware fashion through the song’s lyrics, as well as by featuring fans in the video. The fans were selected for the video because they were able to reach Swift on social media, and the marketing of the viral campaign for the song and video is further facilitated by social media. This demonstrates not only that social media permeates the model of music marketing, but that it has fundamentally altered how artists, such as Taylor Swift, compose their music. The music reflects this culture of social media and interacts with it, both lyrically and visually. This model is in stark contrast to Swift’s earlier works like “Tim McGraw,” which exists in its own self-contained narrative setting. By contrast “Shake It Off” embodies the circular process of music marketing which is facilitated through social media. This new model represents a fundamental shift in how artists construct their persona, as well as their production and marketing methods. Social media provides continuous feedback which artists such as Swift have expertly harnessed and leveraged. Thus, “Shake It Off” takes equal advantage of both defenders and detractors, all the while using social media as the vehicle for the creation and marketing of the cultural product. The impact of this media upon the cultural production of music is further evinced through songs which revolve around celebrity feuds, of which Taylor Swift is a significant proponent.

II. A Tale of Many Feuds: Taylor Swift vs. Katy Perry, Kanye West, and Kim Kardashian

In researching the culture of social media feuds among celebrities, Taylor Swift’s name features prominently. A simple google search reveals extensive sources of entertainment media tracing Taylor Swift’s many public spats with various celebrities. While this in itself is a significant indicator of how social media discourse is firmly entangled with a celebrity’s public image, Swift’s music reveals yet another facet. A record of feuds outlined by Elle Magazine provides a particularly telling feature. Each section tracing Swift’s various public conflicts which have played out over social media ends with a section entitled “Songs That Came Out of It.” These sections contain lists of songs which may or may not allude to various social media conflicts, with very few verified by the Taylor Swift herself.[20] Articles such as these exemplify the phenomenon of artists writing revenge songs and the speculation that accompanies such songs across various platforms of social and digital media. Whether such speculations are accurate or not, the fact that these conversation occur illustrates the linkage between social media and cultural production. I will examine a selection of songs by Taylor Swift, including “Bad Blood,” and “Look What You Made Me Do.”

Bad Blood

Although there had been speculation on previous albums about who Swift’s forlorn ballads of love and betrayal were about, “Bad Blood” from the album 1989 drew an altogether different kind of social media attention. Unlike previous “break-up” songs which dealt with romantic themes, the songs centered on the break-down of a female friendship. Swift began the speculation by hinting that, “For years, I was never sure if we were friends or not. She would come up to me at awards shows and say something and walk away, and I would think, ‘Are we friends, or did she just give me the harshest insult of my life?’” Swift further alleged that the artist in question “basically tried to sabotage an [Swift’s] entire arena tour.”[21] These comments fuelled a firestorm of speculation that the song was about singer-songwriter Katy Perry, who was reported to have recruited Swift’s back-up dancers for her own tour. Katy Perry seemingly “responded” to this speculation by tweeting “Beware of Regina George in sheep’s clothing,” alluding to the chief “mean girl” in the film Mean Girls. Major newspaper and magazine sites published extensive articles outlining the “timeline of the feud,” reading into specific lyrics in the song; Swift used the word ‘ghost’ and Katy Perry has a song with the title ‘Ghost.’[22]

While the song has been widely disseminated on social media, unlike other songs by Taylor Swift, such as “Shake It Off,” which have been analyzed by scholars from various disciplines in terms of racial implications and issues, it has received little scholarly attention, perhaps due to the perception that social media “feuds” are not “serious” academic matters. However, the dissemination of popular music and the manner in which artists like Swift situate themselves in relation to these discourses is not a simple matter of frivolous celebrity gossip. These discussions have also come to fuel the artist’s cultural production and reception. As shall be discussed, Swift has continued the trend of alluding to social media feuds in subsequent albums with increasingly cryptic hints.

“Bad Blood” is a significant indicator of how social media has become enmeshed with artistic output to an unprecedented level. As with “Shake It Off” from the same album, the song was co-authored by Swift, Max Martin, and Shellback.[23] In general, the lyrics are fairly ambiguous, which makes the speculation surrounding the song all the more intriguing. The form of the song is chorus-verse-prechorus-chorus-verse-prechorus-chorus-bridge-chorus. In typical pop song fashion, it opens with the chorus:

’Cause baby, now we’ve got bad blood

You know it used to be mad love

So take a look what you’ve done

’Cause baby, now we’ve got bad blood, hey!

Now we’ve got problems

And I don’t think we can solve ’em

You made a really deep cut

And baby, now we’ve got bad blood, hey! [24]

The lyrics deal with general feelings of betrayal and contain few identifying features within the music itself. As mentioned previously, the only possible allusion that has been speculated upon is the lyric about “ghosts,” which are repeated twice over the course of the bridge, and which take on a more emotional tone with sparse instrumentation. Swift sings: “Band-aids don’t fix bullet holes/You say sorry just for show/ You live like that, you live with ghosts/Band-aids don’t fix bullet holes (hey)/You say sorry just for show (hey)/If you live like that, you live with ghosts (hey)/(Mmm) If you love like that, blood runs cold! (2:40)”[25] Given the relative ambiguity of the song’s lyrics, it is interesting to note how the social media conversation surrounding the song evolved in part through Swift’s own comments about the breakdown of a relationship with a fellow artist who “sabotaged” her arena tour.[26] In hindsight, these comments seem designed to fuel speculation.

This speculation has in essence become an extension of the song itself. Whether it is “true” that the song was written about Katy Perry or not, this idea has been promulgated across social media. Thus, in this paradigm, discourses on social media have become identified—accurately or inaccurately—with the song’s meaning. Take for instance Emily Yahr’s 2014 article which appeared both online and in print in The Washington Post, entitled “Taylor Swift’s Bad Blood: How We Can Tell She’s Singing About Katy Perry” which forges somewhat dubious connections between Swift’s comments and the idea that the song is about Katy Perry. Yahr pairs Swift’s admission that the song is about a fellow female singer-songwriter with the fact that Swift includes a photo of one of her Grammys in the liner notes of the album as solid evidence that the song is directed at Perry as she has never won a Grammy herself.[27]

This assertion is reinforced by Twitter opinions on a screenshot of a Tweet with the photo of the liner notes next to the lyrics to Bad Blood, and a Tweet that reads, “Taylor Swift wrote a song about Katy Perry and then put a picture of a Grammy next to the lyrics. This is next level.”[28] Thus, there are multiple layers of assumed meaning which accompany the song and create contextual implications. In this case, publications employ social media opinions and assumptions to bolster ideas about artists’ compositional practices, in turn crafting narratives which then become a part of the song’s discourse and meaning. This circularity of cultural production and marketing once again reinforces how compositional practices and the dissemination of music have been impacted by the immediacy of social media and the ubiquity of comments, data, and feedback which media outlets can then shape to fit a narrative. This structure impacts how music is produced, promoted, and ultimately disseminated in the public forum.

Look What You Made Me Do

The song “Look What You Made Me Do” is heavily speculated to be about Kanye West. If “Bad Blood” seemed an evasive nod by Swift to writing about celebrity feuds, her history with Kanye West has led to much bolder musical statements in recent years. The longstanding feud between Taylor Swift and Kanye West has all the makings of a classic revenge song. The story began in 2009 at the MTV Video Awards, where West charged the stage and interrupted Swift’s speech for “Best Female Video of the Year,” stealing the microphone to state his opinion that Beyoncé’s video should have won the category. West’s disruption of Swift’s speech with the words “imma let you finish,” by which he meant that he would allow her to finish her speech only after first interrupting to give his view on the superiority of Beyoncé’s video, has been immortalized in a variety of internet memes. These most often feature a photo of West, along with this phrase, applied to any number of contexts in which someone, or something, is being unceremoniously interrupted (See Figure 3).[29] The incident was prominently featured on entertainment news media.’

Figure 3

While the pair reconciled in 2015, the drama resurfaced in 2016 over his song “Famous,” which contained the lyrics “I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex / Why? I made that bitch famous.” Controversy subsequently abounded, with Taylor’s representation claiming she never approved the lyrics.[30] Kim Kardashian, the wife of Kanye West, then stepped in and released a video of West and Swift speaking over the phone and Swift approving at least part of the lyrics.[31] Swift subsequently fired back saying that she never agreed to be called “that bitch” in the song and added, “I would very much like to be excluded from this narrative.”[32] These words would soon reappear in the music video for her own revenge song “Look What You Made Me Do.” As with the presumed Katy Perry feud, social media has played an integral part in disseminating the conflict, reading into lyrics, and publishing extensive timelines.[33] This demonstrates once again that not only has social media become intertwined with celebrity culture, but with an artist’s output. The song “Look What You Made Me Do,” released on Swift’s 2017 album Reputation exemplifies this complex relationship between music and social media, as well as how Swift employs intertextuality with social media, and even with her own past personas, to produce and market her music.

“Look What You Made Me Do” was viewed by music critics, such as Rollingstone Magazine, as an addition to Swift’s oeuvre of revenge songs, building upon songs like “Bad Blood.”[34] However, unlike “Bad Blood”, which is arguably more ambiguous lyrically, “Look What You Made Me Do” is much more bold and overt in its references to West. The song begins with a reference to the tilted stage he used in his 2016 Saint Pablo tour. Swift sings: “I don’t like your tilted stage (0:19).”[35] Additionally, the melody is primarily syllabic, with emphasis on each syllable throughout the verse creating a declamatory and confrontational feeling to the music, as Swift repeats “No I don’t like you” twice in each verse.[36]

The imagery from this video underscores the atmosphere of confrontation in the lyrics and music. Gone are the peppy dancers and pastel colours from “Shake It Off,” and in its place is a darker sound, and more ominous settings. For instance, Swift is featured throughout the video dressed in various stereotypical “bad girl” costumes, including a go-go dancer in a prison suit (1:20), and a dominatrix (1:50).[37] Nevertheless, there are some intertexual references to the “Shake It Off” video. One of the most notable call-backs is the entourage of dancing Taylor Swift fans. Unlike the previous video, in which Swift enlisted real-life fans, or “Swifties,” “Look What You Made Me Do” features an assembly line of professional male dancers, each adorned in crop tops which bear the insignia “I love T.S (2:10).”[38]

The video opens with dark crows sweeping over a graveyard. The camera pans to a tombstone that reads, “Here Lies Taylor Swift’s Reputation.” Swift appears as a zombie version of herself, crawling from the grave (0:19). From here the scene changes to an opulent gothic-style mansion, with Swift seated at a throne as she sings, “Honey, I rose up from the dead, I do it all the time (0:51).”[39] The scene features the first instance of thematic intertexuality between the video and Swift’s social media marketing campaign for the album’s release. Swift stunned fans by “blacking out” her social media in the days leading up to the album release date and removing all of her photos and Tweets. She returned to social media by gradually featuring three silent clips of a snake.[40] The “resurrection” scene in the mansion post-graveyard features extensive use of the snake motif, from candleholders to Swift’s rings, and even literal snakes slithering at her feet (0:50). This symbolism tacitly references her feud with Kayne West and Kim Kardashian.[41] Around the time Kardashian uploaded the video allegedly proving that Swift had approved the lyrics to “Famous,” she tweeted a series of snake emoticons. This has been read by Swift’s and Kardashian’s fans as a symbolic reference to Swift herself as a cunning and traitorous snake. Like the timelines of feuds, this snake imagery has been analyzed exhaustively by various entertainment publications.[42] This usage of visual motifs across media platforms once again exemplifies the influence of social media upon the artist’s cultural production.

The song as a whole can be viewed as a statement of Swift’s total break from her previous “nice girl” image, made explicit in the bridge of the song. Swift sings “I don’t trust nobody and nobody trusts me/I’ll be the actress starring in your bad dreams (2:20).”[43] As she sings this repeated rhyming couplet, the camera pans over to a mosh pit filled with various clones of Swift at various points in her career, which she kills by standing atop the pile.[44] To reinforce this imagery, the middle eight bars of the song feature Swift talk-singing the lyrics “I’m sorry, the old Taylor can’t come to the phone right now” (Ooh, look what you made me do) “Why?” (Look what you made me do) “Oh, ’cause she’s dead!” (oh!) (2:55).”[45]

While the “mosh pit” of old Taylors is visually compelling, the most vivid example of intertexuality comes at the end of the video where particularly memorable “Old Taylors” line up in front of a jet emblazoned with the album’s title Reputation (3:37).[46] Notably present is “Country Taylor,” with whom this paper began. Her one line is a drawn out “Y’all…” As she says this, the other Taylors immediately pounce on her, parroting various criticisms that Swift received in that phase of her career: “Oh stop acting like you’re all nice. You are so fake.” Says Red album tour-era Taylor. At this, country Taylor breaks down in tears. “Oh there she goes, playing the victim, again.” Says “biker girl” Taylor. It is notable that “Country Taylor” speaks in a contrived “country” accent, seemingly reflecting Swift’s own self-awareness of how she curated her image at that early stage.[47] While “Country Taylor” is compelling, the most significant “Taylor” in terms of intertexual references between music and social media is “2009 MTV Video Awards show Taylor.”

Swift places herself in the line of Taylors dressed in the same attire she wore when Kanye West interrupted her 2009 speech. She then tellingly reiterates the exact phrase with which she ended her Instagram post about the feud: “I would very much like to be excluded from this narrative.” “OH SHUT UP!” the other Taylors snap in return (4:04).[48] Thus, the spoken portion of the music video is perhaps even more significant than the music itself. In this scene, Swift leaves no doubt that she is aware of the various personas she has crafted throughout her career, as well as how social media conversations surrounding these personas have evolved over time. Whether one enjoys her music or not, it is a brilliant method of controlling the information and stories by reclaiming the various “Taylors” she has been, and mocking herself, while simultaneously conveying the message that she is ultimately in control of the “Taylor” she chooses to portray. This indeed seems to continue the thread begun with “Shake It Off,” which similarly beats her critics to the proverbial punchline by expressing her awareness of “what people say.” Thus, the production, visual marketing, and dissemination of “revenge songs” once again illustrates the impact of social media upon the artist’s compositional practices, as well as the circularity of the creative process and subsequent reception of popular music.

While celebrity gossip may appear trivial on the surface, social media discourses surrounding popular music have indeed altered how music is produced and marketed. Artists like Taylor Swift are keenly aware that their music will be analyzed at length for any covert or overt allusions to their various feuds with other celebrities. The increasing boldness with which Swift has referenced such events, as well as her own public comments, and even her encoding of symbols like snakes, displays the interconnectivity of music and social media, to such a degree that media outlets regularly cull lyrics for prospective meaning and publish detailed timelines of celebrity feuds which are interwoven with the analysis of songs these events inspired. As such, the social media discourses surrounding artists’ public personas must be regarded as highly significant in terms of the music they produce, and in some cases even as a catalyst for altering the nature of how artists compose and market their work.

III. From “Rookie” to “Swiftie”: The Evolution of Taylor Swift Fandom

A key facet of Taylor Swift’s long-term fame has been the diehard support of her fanbase. As Adriane Brown writes, fans feel a “personal” connection to Swift, and continuously suture her musical and extramusical personalities together.[49] Brown introduced herself as a researcher and surveyed fans and spent four months in 2012 observing two fan forums, Taylor Swift’s official fan forum, Taylor Connect, and another popular fan-produced forum, Amazingly Talented. [50]

The present study was originally conceived as a continuation of this social experiment by Brown to explore how fan perceptions of Swift have shifted, or whether they have shifted, since 2012, when she had yet to release either of her pop crossover albums, 1989 or Reputation. However, an even more interesting prospect emerged when Swift closed down her long-running fan forum and replaced this with her app, The Swift Life, to coincide with the release of the Reputation album in November, 2017. As such, this section will trace the shift from fan forum to app. I will first discuss the content and structure of the original Taylor Connect application, using the Internet Archive Wayback Machine.[51] This site provides access to fan content. However, this is dependent on screen shots taken on past dates, which are not always available. To counter this challenge, I will use Brown’s article which analyzes fan responses. This will serve as a hybrid snapshot of 2012 and 2017 before the application was shut down. I will then analyze The Swift Life application through my own experiences navigating the site. I argue that The Swift Life enables Swift to control her persona, content, and narrative to an unprecedented level, and to direct the fan experience through its design and infrastructural elements. It also enables her to carefully control her image. As the app was released with the Reputation album, it primarily documents her image from this point in her career onward, providing a clean slate in terms of content, while erasing previous content from Taylor Connect. I will explore how the app controls fan interactions with Taylor Swift through social media capital in the form of ‘likes’ and fan-to-fan relationships, enacting a linear model of fan engagement.

Taylor Connect

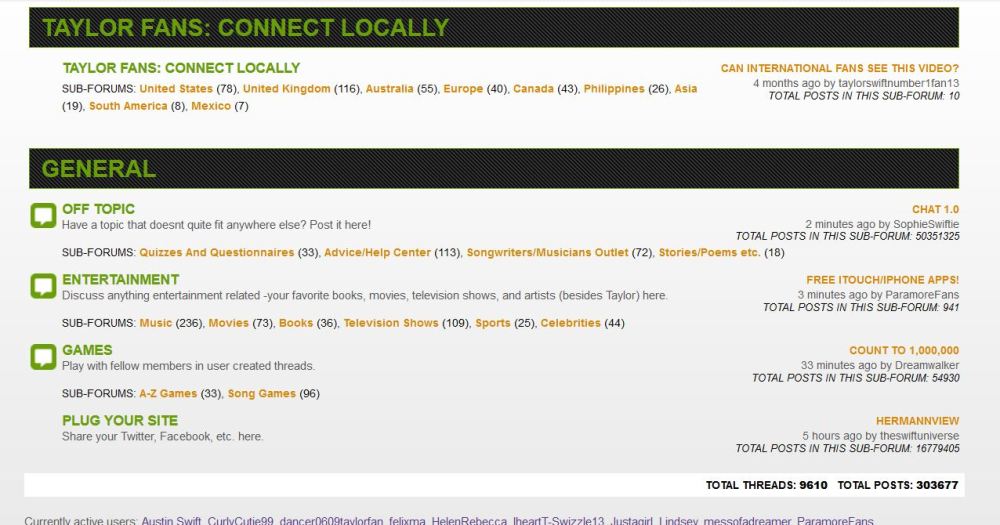

One of the primary features of Taylor Connect, known simply as the “Fan Forum” section of Swift’s official website after 2012, was its open content model, which enabled fans to freely create content. As the forum was hosted on her official website, this openness also provided the benefit of giving Taylor Swift and her team access to a plethora of information and statistics about her fans, which they disclosed willingly. From the beginnings of the forum in 2010 to the closing of the forum in 2017, the “off-topic” thread remained constant, giving fans a place to discuss their personal lives and interests outside of Taylor Swift (See Figures 4 and 5).[52]

Figure 4: August 6, 2010 Screenshot showing “Off-Topic” Section

Figure 5: Screen shot demonstrating “Off-Topic Section” as of July 10, 2017

Thus, this model appears to have provided Taylor Swift and her team a considerable amount of information about her fans. As Adriane Brown observes in her analysis of the Taylor Connect forum in 2012, a core aspect of Swift’s fan appeal is her ability to appear “authentic” and “normal.” This “normalcy” is tied to her status as a white, middle class, heterosexual, normatively feminine girl. Yet paradoxically, this idea of “authenticity” is commodified, as it is linked to Swift’s ability to generate sales of her music and other merchandise. Thus, Swift’s relatability as a ‘typical’ American girl is in actuality heavily contrived and commercialized, making it anything but typical.[53] In light of this “relatable” image, it is worth considering the impact that her fan forum content may have had. Her team would have been capable of performing targeted searches, reading through posts, and even posting topics to gather information and statistics. Thus, Taylor’s “personal” connection to her fans could easily be constructed by tracking their patterns of consumption, interests, likes and dislikes, enabling her to curate her persona in relation to this information.

Another feature which remained stable for the duration of the fan forum was the section thread on lyric interpretation (See Figures 6, 7, and 8).[54] This is perhaps not surprising given how passionately fans and even the entertainment media debate Taylor Swift’s lyrics and search for coded meanings. However, what is perhaps unexpected is the specificity with which the idea of reading into lyrics is suggested in the thread descriptions. While the 2010 forum describes the thread in a generic manner, there is a marked shift by 2012, which contains the text “Dissect song meanings.” This wording remains up to the final version of the forum in 2017.[55]

Figure 6: Music thread, August 10, 2010

Figure 7: Music thread in 2012 with more cryptic suggestion to dissect song meanings

Figure 8: Identically-worded Music section in 2017

This wording indicates that there is an awareness of the manner in which fans “dissect” lyrics. As discussed in the previous section, Taylor Swift herself has played into rumours about the meanings of her song lyrics, feeding her social media presence into her videos.[56] As Brown points out, Swift’s lyrics and music played a key role in crafting her image as a “normal” girl in 2012, prior to her dramatic image change with the 1989 album. It is fascinating to observe Brown’s analysis in 2012, which highlights fan forum responses idealizing Swift for her country music, sexual purity, and post-racial views, and to contrast this with her image today.[57] Thus, encouraging fans to read into meanings behind lyrics once again demonstrates circularity between artist, fans, and industry that aligns with the Hughes, Evans, Morrow, Keith model.[58] There is a continuous feedback loop that enables Swift to gather information about her fans, track their likes and dislikes, and use this information to formulate marketing strategies by virtue of this participatory culture of fandom. This impacts every aspect of Swift’s production and marketing model, down to her allusions to social media rumours in songs and music videos.

The Swift Life – Toward a New Linear Model

In November, 2017 Taylor Swift released her mobile phone app, Taylor Swift: The Swift Life, which was developed by the mobile game developed, Glu Mobile.[59] In the months leading up to its launch, the Taylor Connect community received a notification that the forum was closing down “to make way for The Swift Life App” (See Figure 9).[60] Thus, the app completely replaced a community that had been active since 2010, regardless of the fact that the forum and the app were different mediums that could have co-existed with one another. This appears to have been a method of funnelling fan traffic without risking the established community choosing not to migrate over to the app. This decision signals a shift toward a more linear method of controlling fan traffic and interactions. The Swift Life app can be seen as representing a new linear model for artist social media marketing. The app is carefully designed to manage fans, as well as fan-to-fan and fan-to-artist interactions through the construction of hierarchies of fans and the infrastructure of the app. These two elements are facilitated through the encoding of symbolism, and the use of invented terminology. It should be noted that Swift is not the first celebrity to introduce this kind of app. Previous examples also produced by Glu Mobile include Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, and Restaurant Dash with Gordon Ramsay.

Figure 9

However, while Kim Kardashian’s and Gordon Ramsay’s apps are overtly marketed as games, Swift’s app is instead promoted as a fan platform and social network. In spite of this marketing angle it is listed on the Glu website under “games.”[61] This suggests that Swift may want to downplay the gaming aspects of the app, which upon closer inspection, appear designed to shift fan interactions toward a more carefully controlled linear model.

The Swift Life app carefully manages fan interactions through the construction of hierarchies of fans. Tiers of fandom are a central feature. Fans advance through five categories of fandom, each with approximately five levels, from the beginner level, Rookie, to Fan, Superfan, Swiftie, and the highest tier, Super Swiftie (See Figure 10).[62] Levels of fandom increase by fulfilling tasks, such as liking fan posts or Taylor’s posts. Completing tasks earns music notes, which unlock packs of Taymojis, the app’s terms for emojis meshed together with Taylor’s name (See Figure 11).[63] After a number of tasks are completed, a player’s level increases from Rookie Level 1 to Rookie Level 2 until they eventually progress to the next tier of fandom. At each new level, new rewards, such as different kinds of Taymojis are unlocked. Taymojis feature various recognizable symbols associated with Swift’s life career, such as song titles (see figure 12).[64]

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Thus, fan engagement is controlled in a linear manner through the construction of hierarchies of fans. These hierarchies in turn give Swift valuable information about fan demographics, as well as levels of fan engagement with the app.

The infrastructure of the app further facilitates linear fan engagement. Upon downloading the app, Taylor herself walks new users through its structure (See Figure 11).[65] While fans are permitted to post their own content, it is structured in a similar manner to Instagram, in that users can only comment on each others posts and they must post in a photo format. As such, it is considerably less open than the fan forum model which enabled users to freely generate content and post comments on each other’s posts. Moreover, users must build a social network by requesting friends in order for others view their content. Again, this is far more linear in structure than fan forums like Taylor Connect, where anyone browsing the internet can read posts, and any user on the forum can see and comment on content that is posted.

Another linear aspect of the app is the inclusion of “Taylor’s Feed,” which consists of posts that Taylor Swift has herself posted, as well as fan posts. Fan posts are vetted through an informal fan nomination process known as a “Swiftsend.” As with “Taymojis,” Swift places her personalized “stamp” on the features of the app. If a fan sees another fan’s post that they think Taylor herself would want to see, they can opt to click the “Swiftsend” button to increase the odds that Taylor will see and ‘like’ the post.[66] Thus, in order to garner enough Swiftsends to send a post to Taylor Swift, a user must like enough posts, gather enough friends, and in sum, establish enough social capital to be able to wield the amount of Swiftsends needed to catch Taylor’s attention and have her ‘like’ the post. This exemplifies how the linear model operates in action. The fan who aspires to “connect” with Taylor has to go through many steps and invest a considerable amount of time and energy using the app to do so. The appeal of seeking increased ‘levels’ of fandom on the app is additionally reinforced by how fans engage with posts that Taylor ‘likes.’ The select few who receive a ‘like’ from Swift herself receive broad social recognition on the site, with other users offering their congratulations for having captured the coveted attention of their hero, Taylor Swift (See Figure 12).[67]

Figure 13

Figure 14

This then increases the odds of other fans wanting to achieve this milestone on the site and go through the necessary process to do so. This linear model enables Swift to carefully control which of her fans’ posts receive widespread exposure through her feed, allowing her to curate how fan content contributes to her image. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the vast majority of fan posts that Taylor ‘likes’ are feel-good fan stories of how she has inspired them (See Figure 13 for a typical example). Thus, The Swift Life embodies a shift toward a new linear model, whereby artists have begun to reclaim their social media presence through self-contained fan networks. These networks are designed in such a way as to carefully control fan engagement, as well as how the artist curates narratives of their life and career.

Conclusion

From the classic linear model of marketing in the pre-social media age, to the circular model, and toward a new linear model of social media engagement, the pop star’s social media presence has become intertwined with the production, marketing, and reception of their music to an unprecedented level. Employing Taylor Swift as a case study, this project has explored this phenomenon in terms of the cultivation of persona, celebrity feuds, and fandom through selected songs and music videos, various digital and social media platforms, and in interviews entertainment news articles. Social media has altered the cultural landscape of music to such a degree that it takes an effort to remember the music industry before it. Taylor Swift’s starry nights in the Deep South seem a distant memory.

Through apps like Taylor Swift: The Swift Life, artists are once again evolving, this time away from the circular model, and constructing new linear, self-contained platforms that enable them once again to control modes of fan engagement. While the future of music and social media is as transitory as the nature of technological development itself, it seems certain that the days of the carefully scripted artist interview are a remnant of the past. Music is increasingly reflecting the omnipresence of social media, and artists like Taylor Swift have expertly harnessed the continuous loop of fan feedback and access it provides. Thus, it seems that Swift herself, for all her posturing to the contrary, would in fact like to be anything but “excluded from this narrative.”

Notes

[1]. “Time out with Britney Spears Part 1 – Intro + Growing Up HD,” YouTube Video, 9:32, posted by “BritneyFansSite,” August 2, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXrSSFRjtEo.

[2]. Ibid.

[3]. “Baby One More Time Hidden Track/ Britney Talks About the Backstreet Boys,” YouTube Video, 2:24, posted by “x_toxicity,” January 6, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Aki5lBzvHk.

[4]. Diane Hughes, Mark Evans, Guy Morrow, and Sarah Keith, The New Music Industries: Disruption and Discovery (Sydney: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 29.

[5]. Ibid., 30.

[6]. “Taylor Swift Biography,” Biography, accessed January 18, 2018, https://www.biography.com/people/taylor-swift-369608.

[7]. “Official Home Page – http://www.taylorswift.com,” Internet Archive Wayback Machine, June 8, 2002, https://web.archive.org/web/20020608133250/https://www.taylorswift.com/.

[8]. For a typical example of this debate, including those who staunchly defend Swift’s country accent as “authentic,” see “Taylor’s “Fake” Country Accent,” Reddit, accessed February 12, 2018, https://www.reddit.com/r/TaylorSwift/comments/78hadv/taylors_fake_country_accent/.

[9]. In this 2006 interview, Swift is asked where she is from. After stating that she is from Pennsylvania, she is quick to point out that she moved to Hendersonville Tennessee a few years back and to praise “Southern hospitality”. See “Taylor Swift Country Weekly Interview 2006,” YouTube Video, 2:21, posted by “aussiemileyfan,” March 14, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DToWgXq83HM. When compared to her current accent and image, the differences are quote striking: “Taylor Swift Latest Interview 2018,” YouTube Video, 11:17, posted by “Hollywood Times,” March 6, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l-U_eONQtmE.

[10]. Travis Stimeling, “Taylor Swift’s “Pitch Problem” and the Place of Adolescent Girls in Country Music,” in Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music, eds. Diane Pecknold and Kristine M. McCusker (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2016), 89.

[11]. “Taylor Swift Lyrics: Tim McGraw,” AZlyrics, accessed January 24, 2018, https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/taylorswift/timmcgraw.html.

[12]. “Taylor Swift – Tim McGraw,” YouTube Video, 3:51, posted by “Taylor Swift,” June 16, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GkD20ajVxnY. For information on Southern diction see Robert Blumenfeld, Accents: A Manual for Young Actors (New York: Limelight Editions, 2002), 145.

[13]. Ibid.

[14]. Ibid.

[15]. “Taylor Swift Interview 2014: Singer Premieres ‘Shake It Off,’ Announces New Album,” YouTube Video, 4:53, posted by “ABC News,” August 14, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AM9sq93pXVg.

[16]. “Taylor Swift Lyrics: Shake It Off,” AZlyrics, accessed January 28, 2018, https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/taylorswift/shakeitoff.html.

[17]. “Taylor Swift Interview 2014: Singer Premieres ‘Shake It Off,’ Announces New Album,” YouTube Video.

[18]. Clyde Philip Rolston, Amy Macy, Tom Hutchison, and Paul Allen, Record Label Marketing: How Music Companies Brand and Market Artists in the Digital Era (New York: Focal Press, 2016), 85.

[19]. “Taylor Swift Interview 2014: Singer Premieres ‘Shake It Off,’ Announces New Album,” YouTube Video.

[20]. Alyssa Bailey, “The Complete History of Everyone Who’s Had Bad Blood With Taylor Swift,” Elle Magazine, May 9, 2017, https://www.elle.com/culture/celebrities/a37995/taylor-swift-anti-squad-members/.

[21]. Ibid.

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. “Taylor Swift – Shake It Off,” AllMusic, accessed February 16, 2018, https://www.allmusic.com/album/shake-it-off-mw0002725966/credits.

[24]. “Taylor Swift Lyrics: Shake It Off,” AZlyrics, accessed January 28, 2018, https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/taylorswift/shakeitoff.html.

[25]. Ibid.

[26]. Alyssa Bailey, “The Complete History of Everyone Who’s Had Bad Blood With Taylor Swift,” Elle Magazine.

[27]. Emily Yahr, “Taylor Swift’s ‘Bad Blood’: How we can tell she’s singing about Katy Perry,” The Washington Post, October 27, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2014/10/27/taylor-swifts-bad-blood-how-we-can-tell-shes-singing-about-katy-perry/?utm_term=.e535f587f780.

[28]. Ibid.

[29]. “Kanye West ruins Taylor Swift’s VMA Moment 2009,” YouTube Video, 1:29, posted by “EduardovV1,” September 15, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z4xWU8o2cvA. For an example of the meme, see “Kanye Interrupts / Imma Let You Finish,” Know Your Meme, accessed February 17, 2018, http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/kanye-interrupts-imma-let-you-finish and “Severus Snape – Image #225,398,” Know Your Meme, accessed February 17, 2018, http://knowyourmeme.com/photos/225398-severus-snape/.

[30]. Ashley Monae, “Kanye & Kim or Taylor Swift: Who Won the Feud? Media Critics Weigh In,” Billboard, July 19, 2016, https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/7439506/kanye-west-kim-kardashian-taylor-swift-feud-won.

[31]. Alyssa Bailey, “The Complete History of Everyone Who’s Had Bad Blood With Taylor Swift,” Elle Magazine.

[32]. While the original Instagram post by Taylor Swift was removed when she blacked out her social media prior to the release of her Reputation album, a screen capture can be found at, Zaynab Quadri “What we learnt from singer’s fight with Kanye West and Kim Kardashian,” Pulse.ng, July 19, 2017, http://www.pulse.ng/gist/pop-culture/taylor-swift-wins-the-internet-id5282190.html.

[33]. As an example, see Brittany Spanos, “Taylor Swift Releases Apparent Kanye West Diss Song ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ First ‘Reputation’ single seemingly revives dormant feud over controversial “Famous” lyric,” Rollingstone, August 24, 2017, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/taylor-swift-new-song-look-what-you-made-me-do-apparent-kanye-west-diss-w499090.

[34]. Ibid.

[35]. Ibid.

[36]. “Taylor Swift Lyrics: Look What You Made Me Do,” AZlyrics, accessed February 23, 2018, https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/taylorswift/lookwhatyoumademedo.html.

[37]. “Taylor Swift – Look What You Made Me Do,” YouTube Video, 4:15, posted by “Taylor Swift,” August 27, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3tmd-ClpJxA.

[38]. Ibid.

[39]. Ibid.

[40]. Raisa Bruner, “The Internet Is Very Excited About This Cryptic Video Taylor Swift Just Shared,” Time, August 21, 2017, http://time.com/4908923/taylor-swift-snake-tweet/.

[41]. “Taylor Swift – Look What You Made Me Do,” YouTube Video, 4:15, posted by “Taylor Swift,” August 27, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3tmd-ClpJxA.

[42]. Some of the many examples include, Bianca Giulione, “A Brief History of Taylor Swift’s Snake Reputation,” Highsnobiety, August 25, 2017, https://www.highsnobiety.com/2017/08/25/taylor-swift-snake-history-reputation/, and Raisa Bruner, “Taylor Swift Has a History With Snakes: Here’s the Whole Backstory,” Time, August 24, 2017, http://time.com/4914211/taylor-swift-snakes-timeline/.

[43]. “Taylor Swift Lyrics: Look What You Made Me Do,” AZlyrics.

[44]. This article does a thorough job of detailing all of the various ‘Taylors’ killed off in the video. See Dee Lockett, “Every ‘Old Taylor’ Taylor Swift Killed in the ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ Video,” August 29, 2017, http://www.vulture.com/2017/08/every-old-taylor-taylor-swift-killed-in-her-lwymmd-video.html.

[45]. “Taylor Swift Lyrics: Look What You Made Me Do,” AZlyrics.

[46]. “Taylor Swift – Look What You Made Me Do,” YouTube Video, 3:41, posted by “Taylor Swift,” August 27, 2017, https://youtu.be/3tmd-ClpJxA?t=3m41s.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. Ibid.

[49]. Adriane Brown, “‘She isn’t whoring herself out like a lot of other girls we see’: Identification and “Authentic” American Girlhood on Taylor Swift Fan Forums,” Networking Knowledge 5, no. 1 (2012): 161.

[50]. Ibid., 164.

[51]. It should be noted that the fan forum was known as “Taylor Connect” until February 2012, when it was changed to the more generic “Fan Forum.” Over the years, graphics and forum titles changed, but the forum was featured in the same space on Swift’s official website.

[52]. “Taylor Connect,” Internet Archive Wayback Machine, August 6, 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20100806123802/http://taylorconnect.com/, “Forum,” Internet Archive Wayback Machine, July 10, 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20170710074926/http://taylorswift.com/forum/.

[53]. Adriane Brown, “‘She isn’t whoring herself out like a lot of other girls we see’: Identification and “Authentic” American Girlhood on Taylor Swift Fan Forums,” 162.

[54]. “Taylor Connect,” Internet Archive Wayback Machine, August 10, 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20100810174555/http://taylorswift.taylorconnect.com:80/forum, “Forums,” Internet Archive Wayback Machine, June 17, 2012, https://web.archive.org/web/20120617173016/http://taylorswift.com/forum/, “Forum,” Internet Archive Wayback Machine, July 10, 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20170710074926/http://taylorswift.com/forum/.

[55]. Ibid.

[56]. “Taylor Swift – Look What You Made Me Do,” YouTube Video, 3:41, posted by “Taylor Swift,” August 27, 2017, https://youtu.be/3tmd-ClpJxA?t=3m41s.

[57]. Adriane Brown, “‘She isn’t whoring herself out like a lot of other girls we see’: Identification and “Authentic” American Girlhood on Taylor Swift Fan Forums,” 167.

[58]. Diane Hughes, Mark Evans, Guy Morrow, and Sarah Keith, The New Music Industries: Disruption and Discovery (Sydney: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 30.

[59]. “The Swift Life,” Glu Mobile Inc., accessed March 3, 2018, https://www.glu.com/games/the-swift-life/.

[60]. “Taylor Connect Community,” Internet Archive Wayback Machine, November 25, 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20171125003441/https://taylorconnect.com/community.

[61]. The promotional video for The Swift Life does not mention the app as a “game,” and instead focuses on the social networking elements of fans connecting with Taylor and with other fans. See “The Swift Life,” Glu Mobile, accessed March 3, 2018, https://www.glu.com/games/the-swift-life/. For the celebrity game apps mentioned see “Featured Games,” Glu Mobile Inc., accessed March 7, 2018, https://www.glu.com/games/.

[62]. Glu Mobile Inc., Taylor Swift Materials: Taylor Swift Productions Inc., “Taylor Swift: The Swift Life,” Google Play, Vers. 1.4.0 (2017), https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.glu.fun, accessed on March 19, 2018. Fr a description of fan levels, see: Elana Fishman, “Taylor Swift’s new app stole my emoji idea and hours of my life,” The Verge, December 20, 2017, https://www.theverge.com/2017/12/20/16799924/taylor-swift-app-review-the-swift-life.

[63]. Ibid.

[64]. Ibid.

[65]. Ibid. For a fan review with a through walk-through of the app, see also “The Swift Life – Reaction and Review!” YouTube Video, 9:55, posted by “Stevie-L,” December 23, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvKKDWRa2bc. At 2:44, this fan aptly expresses their confusion over the app being both a social media network and a game, exclaiming “This is the weirdest app I’ve ever used in my entire life!”

[66]. See “The Swift Life – Reaction and Review!” YouTube Video, 9:55, posted by “Stevie-L,” December 23, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvKKDWRa2bc at 6:06.

[67]. Glu Mobile Inc., Taylor Swift Materials: Taylor Swift Productions Inc., “Taylor Swift: The Swift Life,” Google Play, Vers. 1.4.0 (2017), https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.glu.fun, accessed on March 23, 2018.

Bibliography

“Baby One More Time Hidden Track/ Britney Talks About the Backstreet Boys.” YouTube Video. 2:24. Posted by “x_toxicity.” January 6, 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Aki5lBzvHk.

Bailey, Alyssa. “The Complete History of Everyone Who’s Had Bad Blood With Taylor Swift.” Elle Magazine. May 9, 2017. https://www.elle.com/culture/celebrities/a37995/taylor-swift-anti-squad-members/.

Bruner, Raisa. “Taylor Swift Has a History With Snakes: Here’s the Whole Backstory.” Time, August 24, 2017. http://time.com/4914211/taylor-swift-snakes-timeline/.

—. “The Internet Is Very Excited About This Cryptic Video Taylor Swift Just Shared.” Time. August 21, 2017,. http://time.com/4908923/taylor-swift-snake-tweet/.

Blumenfeld, Robert. Accents: A Manual for Young Actors. New York: Limelight Editions, 2002.

Brown, Adriane. “‘She isn’t whoring herself out like a lot of other girls we see’: Identification and “Authentic” American Girlhood on Taylor Swift Fan Forums.” Networking Knowledge 5, no. 1 (2012): 161-180.

“Featured Games.” Glu Mobile. Accessed March 7, 2018. https://www.glu.com/games/.

Fishman, Elana. “Taylor Swift’s new app stole my emoji idea and hours of my life.” The Verge. December 20, 2017. https://www.theverge.com/2017/12/20/16799924/taylor-swift-app-review-the-swift-life.

“Forum.” Internet Archive Wayback Machine, July 10, 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170710074926/http://taylorswift.com/forum/.

“Forums.” Internet Archive Wayback Machine. June 17, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120617173016/http://taylorswift.com/forum/.

Giulione, Bianca. “A Brief History of Taylor Swift’s Snake Reputation.” Highsnobiety. August 25, 2017. https://www.highsnobiety.com/2017/08/25/taylor-swift-snake-history-reputation/.

Glu Mobile Inc., Taylor Swift Materials: Taylor Swift Productions Inc. “Taylor Swift: The Swift Life.” Google Play. Vers. 1.4.0 (2017). https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.glu.fun. Accessed on March 19, 2018.

Hughes, Diane, Mark Evans, Guy Morrow, and Sarah Keith. The New Music Industries: Disruption and Discovery. Sydney: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

“Kanye West ruins Taylor Swift’s VMA Moment 2009.” YouTube Video. 1:29. Posted by “EduardovV1.” September 15, 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z4xWU8o2cvA.

“Kanye Interrupts / Imma Let You Finish.” Know Your Meme. Accessed February 17, 2018. http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/kanye-interrupts-imma-let-you-finish.

Lockett, Dee. “Every ‘Old Taylor’ Taylor Swift Killed in the ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ Video.” August 29, 2017. http://www.vulture.com/2017/08/every-old-taylor-taylor-swift-killed-in-her-lwymmd-video.html.

Monae, Ashley. “Kanye & Kim or Taylor Swift: Who Won the Feud? Media Critics Weigh In.” Billboard. July 19, 2016. https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/7439506/kanye-west-kim-kardashian-taylor-swift-feud-won.

“Official Home Page – http://www.taylorswift.com.” Internet Archive Wayback Machine. June 8, 2002. https://web.archive.org/web/20020608133250/https://www.taylorswift.com/.

Rolston Clyde Philip, Amy Macy, Tom Hutchison, and Paul Allen. Record Label Marketing: How Music Companies Brand and Market Artists in the Digital Era. New York: Focal Press, 2016.

“Severus Snape – Image #225,398.” Know Your Meme. Accessed February 17, 2018, http://knowyourmeme.com/photos/225398-severus-snape/.

Spanos, Brittany. “Taylor Swift Releases Apparent Kanye West Diss Song ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ First ‘Reputation’ single seemingly revives dormant feud over controversial “Famous” lyric.” Rollingstone. August 24, 2017. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/taylor-swift-new-song-look-what-you-made-me-do-apparent-kanye-west-diss-w499090.

Stimeling, Travis. “Taylor Swift’s “Pitch Problem” and the Place of Adolescent Girls in Country Music.” In Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music, edited by Diane Pecknold and Kristine M. McCusker. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2016.

“Taylor Connect.” Internet Archive Wayback Machine. August 6, 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100806123802/http://taylorconnect.com/.

“Taylor’s “Fake” Country Accent.” Reddit. Accessed February 12, 2018. https://www.reddit.com/r/TaylorSwift/comments/78hadv/taylors_fake_country_accent/.

“Taylor Swift Biography.” Biography. Accessed January 18, 2018. https://www.biography.com/people/taylor-swift-369608.

“Taylor Swift Country Weekly Interview 2006.” YouTube Video. 2:21. Posted by “aussiemileyfan.” March 14, 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DToWgXq83HM.

“Taylor Swift Interview 2014: Singer Premieres ‘Shake It Off,’ Announces New Album.” YouTube Video. 4:53. Posted by “ABC News.” August 14, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AM9sq93pXVg.

“Taylor Swift Latest Interview 2018.” YouTube Video. 11:17. Posted by “Hollywood Times.” March 6, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l-U_eONQtmE.

“Taylor Swift – Look What You Made Me Do.” YouTube Video. 4:15. Posted by “Taylor Swift.” August 27, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3tmd-ClpJxA.

“Taylor Swift Lyrics: Look What You Made Me Do.” AZlyrics. Accessed February 23, 2018. https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/taylorswift/lookwhatyoumademedo.html.

“Taylor Swift Lyrics: Shake It Off.” AZlyrics, Accessed January 28, 2018. https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/taylorswift/shakeitoff.html.

“Taylor Swift – Shake It Off.” AllMusic. Accessed February 16, 2018. https://www.allmusic.com/album/shake-it-off-mw0002725966/credits.

“Taylor Swift Lyrics: Tim McGraw.” AZlyrics. Accessed January 24, 2018. https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/taylorswift/timmcgraw.html.

“Taylor Swift – Tim McGraw.” YouTube Video. 3:51. Posted by “Taylor Swift.” June 16, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GkD20ajVxnY.

“The Swift Life.” Glu Mobile. Accessed March 3, 2018. https://www.glu.com/games/the-swift-life/.

“The Swift Life – Reaction and Review!” YouTube Video. 9:55. Posted by “Stevie-L.” December 23, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvKKDWRa2bc.

“Time out with Britney Spears Part 1 – Intro + Growing Up HD.” YouTube Video. 9:32. Posted by “BritneyFansSite.” August 2, 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXrSSFRjtEo.

Quadri Zaynab. “What we learnt from singer’s fight with Kanye West and Kim Kardashian.” Pulse.ng. July 19, 2017. http://www.pulse.ng/gist/pop-culture/taylor-swift-wins-the-internet-id5282190.html.

Yahr, Emily. “Taylor Swift’s ‘Bad Blood’: How we can tell she’s singing about Katy Perry.” The Washington Post. October 27, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2014/10/27/taylor-swifts-bad-blood-how-we-can-tell-shes-singing-about-katy-perry/?utm_term=.e535f587f780.